|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

3. Lighting the town of Margate.

The lack of a proper police force was particularly worrying during the hours of darkness. The lack of street lighting made walking through the town at night a risky undertaking because of the chance of being attacked and robbed, and because the narrow and crooked streets were full of hazards for an unwary pedestrian. Of course, these risks could be avoided by not venturing out at night, but this would not suit Margate’s visitors who expected to be able to enjoy themselves in the evening, and the livelihoods of the many of the town’s inhabitants depended on keeping the visitors entertained. Visitors to Margate, particularly those from London, were used to night-time patrols and street lighting, and would have expected to find them at an up and coming watering place like Margate; the problem for Margate was how to pay for them.

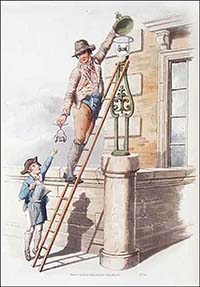

Street lighting, until the end of the seventeenth century, was provided by private individuals placing candles in lanterns outside their houses.1 By the end of the 1730s most large towns had progressed to lighting with public oil lamps in the streets, paid for by a rate charged on properties in the town.2 These oil lamps had a glass or a reflector to enhance their luminosity and were either suspended from brackets projecting from a house front, or hung on posts, being lighted by old men carrying torches up a step ladder.3 It seems unlikely that any such public lighting was provided in Margate until after 1787 when the Act establishing the Margate Improvement Commissioners was passed.4 However, the main streets such as High Street and Cecil Square would not have been completely dark at night because of light spilling out from the shops, which would have been well lighted with large numbers of candles, and, later, with oil lamps.5 The owner of the Assembly Rooms in Cecil Square also took care to illuminate the way to his Rooms. In 1773 he placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette to deny rumours that the New Assembly Rooms and Hotel had been closed, and ‘To prevent the repeated impositions on enquiring strangers, they are requested to observe in the first street [High Street], about two hundred yards down on the right hand, a Board of Directions to the New Assembly Rooms and Hotel, and in the night-time the two lamps will direct them into the Square to the same, where they will be sure to find clean and well-aired beds, &c., until they can provide themselves with private lodgings’.6

At the first meeting of the new Improvement Commissioners in May 1787 a committee was established to ‘consider of the number of watchmen and of the number and proper situation of the lamps to be provided for lighting the town’.7 The Commissioners would, of course, have been aware of clause XLV of the 1787 act which stated:4

the said Commissioners . . . are hereby authorized and impowered from time to time, and at any time or times after the passing of this Act, to purchase, provide, affix, set up, alter, take down, and renew such and so many lamps, of such size and sorts, and in such places and in such manner as shall to them seem necessary or proper, for well and sufficiently lighting all or any of the streets, lanes, highways, and other public passages and places within the said town of Margate, or Parish of Saint John the Baptist, and also to contract with any person or persons for lighting the said lamps, at such seasons of the year and hours of the evenings as they shall judge necessary, and to pay and allow such sums or sums in defraying the expense of lighting, cleaning, supplying, and maintaining the said lamps as they may think proper.

By August the committee had completed a survey of the town and decided that ‘about forty five lamps would be sufficient for the purpose of lighting the town.’ The final decision was to purchase 60 lamps ‘and for the encouragement of individuals to add to the number of lamps it is resolved that in case any of the inhabitants shall think proper to put up any lamp or lamps at their own expense the above Deputation [Committee] be empowered to agree with any such person for the lighting of such lamps by the year at the same time as the Public Lamps shall be lighted at the rate of half a guinea for the first lamp and of one guinea for every additional lamp which the same person shall put up, to be paid to the Treasurer in advance’.7 A week later the locations for the lamps had been decided: 7

Mr Benezet — Mr Wm. Mussareds — Mr Bloxhams Corner — Mr Cobbs Malt House — Mr Sawkins Corner — Fountain Inn — Mr F. Sackett Corner of his Stable — Bridge — Widow of Thomas Rowe — Jeremiah Doughty — John Stranack jun — Mrs Stricker — Peter Wootton — New Room near the Market — Mr Newby’s — Mr Tennants — R. J. Covell’s Store House — Mr Webb Single Post — Mrs Hills Gate — Mr Wm. Stones Corner — Mr Bushell Corner — Mrs Griffens — Mr Goldsmiths Corner — Mrs Tucker’s — Mrs Hopley’s Corner — Mr Mathews — Mr Brown and Chancellor’s — Mrs Shaw’s Wall — Miss Price Corner — Mrs Champain Corner — Angle Corner — Mr Bassett’s Corner Mill Lane — St John’s Place — Mr Pegden Church Field — Mr Plummer Church Field — Mr Cecil’s Corner — Mr Agassez Corner — Mr Surflen No 10 — Mrs Plummer’s — Mr Gimber’s Corner.

The locations for the lamps in this list had to be described in terms of people’s houses as at this time houses in Margate were generally not numbered and many streets were not named. It was not until April 1795 that the Commissioners decided ‘to give names to the streets and lanes in the town of Margate and to number the houses’.8

At the end of the month the Committee heard that the Improvement Commissioners at Canterbury had decided that rather than looking after their lamps themselves, they would contract out the task. 7 The Margate Commissioners decided to do the same, and arranged for an advertisement to appear in the Kentish Gazette: ‘Margate Pier and Pavement Commissioners will meet at the Bull Head, in Market Place, to receive proposals for contracting to light 55 lamps, from 12 September to May following, to be light at sunset and to burn till sunrise’.9 The decision to advertise in just a local paper meant that only local contractors would submit proposals; the Commissioners, in many of their decisions, demonstrated a belief that, wherever possible, jobs should be given to local people, keeping money in the local community. The contract was, in fact, awarded to John Foat, listed in the Universal British Directory for 1791 as a painter; he agreed to light the lamps at ‘two pence halfpenny per lamp per week, the Commissioners finding oil and other requisites for that purpose’. 7 The decision to light the lamps only from September to May, the darkest months, would obviously save money, but might not suit the visitors during the early part of the bathing season. Perhaps for this reason, Mr Cecil (probably James Cecil), responsible for much of the early development of Margate, agreed ‘to pay the Commissioners half a guinea for one lamp to be lighted during the same time as the Publick lamps, and proposed to pay for three other lamps to be lighted during the remainder of the Bathing Season one shilling per week each’. 7

Unfortunately, John Foat did not do a good job and, in January 1788 he ‘was sent for and acquainted with the dissatisfaction of the Commissioners in regard to the lighting of the lamps’. 7 He claimed that the problem was because of the mixture of seal and whale oil supplied by the Commissioners, and they agreed that, in future, he could use seal oil alone. Nevertheless, when the Commissioners came to consider the contract for the following year they decided to place advertisements in the London morning papers as well as in the local Canterbury papers. 7 The contract was now for 100 lamps, with the lamps being lit ‘from 25th August next inclusive to the Monday next preceding the full moon, in the month of March following, omitting one week in each month nearest the full moon’, the lamps being lit at sunset and burning till sunrise the next morning.10 The Commissioners agreed ‘to view the locations where lamps were put up last year — and to see what improvements can be made in the situations of the former lamps and the proper situations for the additional lamps intended to be put up — also to give orders for the placing of additional posts and lamp irons.’ 7 In 1789 the contract was awarded to a Mr George Rogers of 121 White Chapell, St. Lukes, London, at a cost of 13s 9d per lamp, running from 31 August to the end of March, or 12s 6d per lamp, ‘omitting the nights of lighting in the full moon in each month’.8,11,12 George Rogers appointed William Collis to be the lamp lighter in Margate, at a wage of 14s per week.11

The oil lamps would almost certainly have been very dim indeed, and, with just a hundred lamps to light the whole town, much of even the main streets would have remained in darkness; this, though, would have been a great improvement on the complete darkness that prevailed just a few years before. Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys, who visited Margate in 1798, reported in her diary that Margate was ‘well pav'd and lighted,’ and ‘is now become one of the first watering-places in the kingdom’.13 We get a glimpse of one of the oil lamps in a print ’View on the Parade’ published in 1789 [Figure 1] and of two oil lamps mounted on the wall of the Theatre Royal in a print published in 1804 [Figure 2]. The picture of a lamplighter published in W. H. Pyne's The Costume of Great Britain in 1805 [Figure 3] shows a typical lamp with the oil reservoir and wick suspended from the upper edge of the glass globe, topped with a decorative and well-ventilated metal cap.14

As well as paying for lighting, the Commissioners had to pay for the upkeep and improvement of the Pier at Margate, for the roads, and for watching the town. The Commissioner’s income came from the charges (the Droits) paid by the users of Margate Pier, and, unfortunately, this soon proved insufficient to pay for all the planned improvements. In 1796 a meeting of the Parish Vestry was called in St John’s Church to consider ‘the mode of defraying the expense of lighting and lamping the Town of Margate’.8 The meeting agreed that ‘the continuance of lighting is highly essential to the welfare of the Town of Margate, but as it has been represented that the revenue of the pier and pavement cannot in its present state afford the defraying of the whole of that expense’ it was agreed that ‘a subscription in aid of that fund is recommended to the inhabitants at large.’ The Commissioners present at the Vestry meeting (Francis Cobb, sen., John Grubb, John Gyles, Stephen Bassett, Thomas Were, John Brooman, and Jacob Sawkins) agreed to contribute £42 11s, but the long-term outcome of this funding scheme is not known.

By 1800 the costs of lighting the lamps had increased significantly. In that year there were two applicants for the contract, George Rogers who had continued to hold the contract for many years and who offered to do the job at 7d per lamp per week, and Robert Salter, a Margate grocer,15 who offered to do it for 7¼ d per lamp per week.8 Despite the higher cost, the Commissioners decided to award the contract to Robert Salter because ‘during the last two years in which Mr Rogers hath had the contract for lighting the lamps, the contract, notwithstanding repeated complaints and repeated promises of alterations, hath been most shamefully executed.’ The number of lamps in the town gradually increased, to 120 in 1797 and 140 in 1809.16,17

Unfortunately the financial woes of the Commissioners continued to worsen, particularly after serious damage to the Pier in the storms of 1808. The solution adopted was to hive off the Pier into a separate Joint Stock Company, the Margate Pier and Harbour Company, the work of the Margate Improvement Commissioners in future being paid for by a direct charge, a rate, on owners of property in the town. These new arrangements were ratified by an Act of Parliament, ‘An Act for more effectually paving, lighting, watching, and improving the Town of Margate, in the County of Kent,’ passed in 1813.18 Hepfully, the price for lighting the lamps gradually decreased, and in 1814 the contract was let to Messrs Thomas Lansell and John Bayley, a Margate grocer and Margate builder, respectively,19 at 5¾ d per lamp per week.20 Unfortunately the contractors struggled to do a good job at the contracted price and in October, following a number of complaints, it was resolved ‘that the Clerk do give the contractor for lighting the lamps notice that unless the lamps are regularly lighted according to the terms of the contract, the Commissioners will consider themselves compelled to refuse paying the contractor at the end of the season.20

|

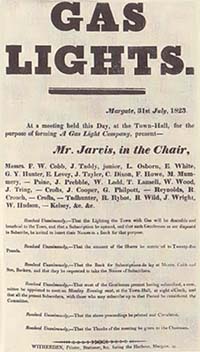

Figure 4. Poster of 1823 calling a meeting in the Town Hall to consider the lighting of Margate by gas. |

A major change in street lighting came in 1824. In March 1823 Mr Israel Gore had approached the Commissioners with a proposition to light the town with gas.21 The Commissioners gave their support, as long ‘as the expense of lighting with gas shall [not] exceed the expense of lighting with oil’.21 In May 1824 the Isle of Thanet Gas Light and Coke Company was established by Act of Parliament and in September 1824 Margate was lighted with gas for the first time.22,23 In April 1825 the Commissioners entered into a contract with the Gas Company to light the town for thirteen years, from 5 July to 15 May each year, at a rate of £2 13s 8d per lamp per year.21 At first there were 98 gas lamps in the town; 21 by 1838 this had increased to 130, but was still less than the number in Ramsgate, where there were 190. Equally shaming, whereas the Ramsgate lamps were lit all year, those in Margate were lit for only about two thirds of the year.24 It also seems that the lamps in Margate were only lit late in the evening, even in winter. A letter written to Cobb in December 1833, signed ‘a Parishioner,’ complained that ‘it is a great neglect, that the town is kept in darkness until 9 o’clock in the evening this time of the year’ and commented on the danger of coaches coming through the ‘narrow and dark streets’ during the winter months.25

The early gas lamps are pictured in a number of prints of Margate of the time [Figures 5-8].

References

1. J. M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London 1600-1750, Oxford, 2001.

2. Peter Borsay, ed., The Eighteenth-century town, 1688-1820, Longman, 1990.

3. Christopher Thomas Richardson, Fragments of History pertaining to the Vill, or Wille, or Liberty, of Ramsgate, Messrs Fuller & Co., Ramsgate, 1885.

4. An Act for rebuilding the Pier of Margate in the Isle of Thanet . . . for widening, paving, repairing, cleaning, lighting, and watching the streets, lanes, highways, and public passages in the town of Margate, 2 Geo III, cap 45, 1787.

5. Dan Cruickshank and Neil Burton, Life in the Georgian City, Viking, 1990.

6. Kentish Gazette, July 14 1773.

7. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners. Volume 1. 6 June 1787 to 12 November 1788, Manuscript, Margate Library.

8. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners. Volume 3 22 January 1794 to 15 December 1802, Manuscript, Margate Library.

9. Kentish Gazette, August 28 1787.

10. Morning Herald, July 18 1788.

11. Kent Archives, U1453/O57/25 Lamp Lighting

12. Oracle Bell’s New World, August 17 1789.

13. Emily J. Climenson, ed., Passages from the Diaries of Mrs. Philip Lybbe Powys of Hardwick House, Oxon. A.D. 1756 to 1808, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1899.

14. W. H. Pyne, The Costume of Great Britain, 1805.

15. The Universal British Directory ofTrade, Commerce, and Manufacture . . . , Champanye and Whitrow, 1791.

16. Kentish Gazette, August 4 1797.

17. Kentish Gazette, July 28 1815.

18. An Act for more effectually paving, lighting, watching, and improving the Town of Margate, in the County of Kent, 21 May 1813 , 53 Geo III, cap 82.

19. Pigot and Co. Directory for Kent, Pigot & Co., 1823.

20. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners Book 5 29 May 1809 to 27 December 1815, Manuscript, Margate Library.

21. Edward White, Extracts from the Minutes of the Margate Commissioners Book 6, 10 January 1816 to 23 January 1833, Manuscript, Margate Library.

22. An act for lighting with gas the towns or villages of Margate, Ramsgate, and Broadstairs, and places adjacent, in the County of Kent, 28 May 1824, 5 Geo. IV, cap lxxv.

23. Kentish Gazette, September 7 1824.

24. Canterbury Journal, December 22 1838.

25. Kent Archives, U1453 060, Correspondence with J. E. Wright, Clerk of Commissioners, Bundle B 1833, Letter to Cobb, December 3 1833.